The conditions of modern office work have made many familiar with the term “ergonomics,” which refers to the study of making working conditions as comfortable and conducive to work as possible. Central to this pursuit is the idea that both the workers’ tools and the workspace itself ought to be constructed to suit the workers. Yet in practice we often find products designed not by end users, but by a small group of professional designers, specialists who may lack firsthand experience of the environment where their product will be used. It’s surprisingly rare to find an industrial designer who draws on his or her own personal difficulties with badly-designed products to make effective, ergonomic ones; Maria Bergson, a secretary who became preeminent in the field of corporate interior design, is one.

Little is known of Bergson’s early life except that she was born in Vienna, Austria, and that in her youth she had a brief acting career. Her first steps toward fame were taken as a secretary for Time Inc. in 1944, four years after she had moved to the United States in her mid-twenties. And those steps began with frustration at a bad office tool.

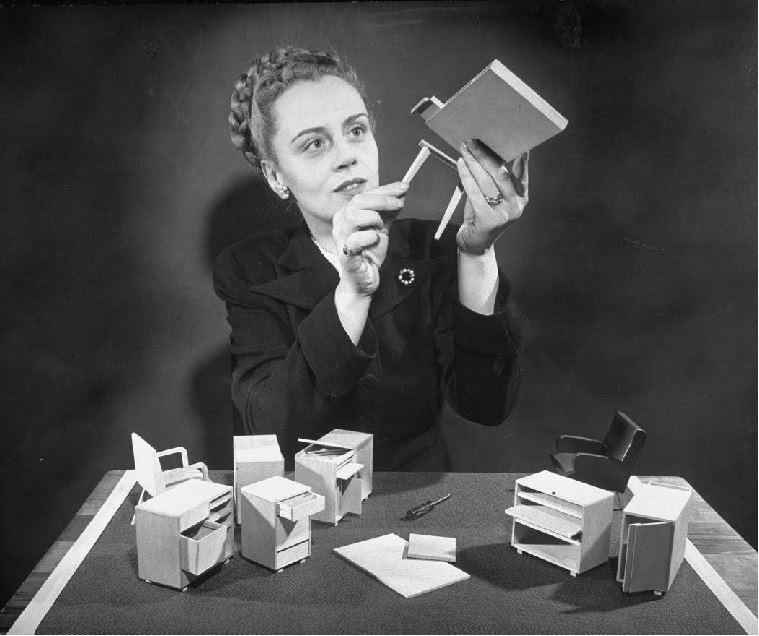

In performing her clerical duties, Bergson found her desk more of a hindrance than a help; she couldn’t reach to the edge, so a large amount of its surface area was wasted, and the drawers were awkward to use and spaced far apart. Rather than find a workaround or simply shrug and accept the inconvenience, Bergson designed a better desk. But it didn’t stop there. Bergson shared many ideas for improving the office with Time executives, who were receptive to the new ideas and suggested that she work them up into detailed plans for the company’s use. Within a few years, Bergson’s clout had grown so much that she was able to open her own design consultancy, Maria Bergson Associates.

Bergson specialized in corporate interior design, creating spaces that combined professionalism with good taste and kept business tools as accessible as possible. One of her proudest achievements was a scheme of partitioned modular workstations designed to keep all the employees’ tools within easy reach, a forerunner of the cubicle system that Herman Miller later made ubiquitous. Bergson’s similar plan was already fully formed by 1949, nearly two decades before the concept swept the office world.

Modularity was a key feature of Bergson’s style in general. She also designed a series of 10 desk pieces that could be combined to create a customized desktop. These pieces were made with a variety of end users in mind, such as one that had many drawers for various office supplies at one end and one or two drawers at the other; one set of drawers was for the executive who would be sitting there all day, the opposite set for a visitor who would need only pencils and paper. Long before IKEA became a phenomenon in the United States, Bergson marketed simple and easily stored furniture that could be adapted to a variety of needs.

Bergson’s unique design ideas made her a minor celebrity in her time. She was the first female designer to appear in Who’s Who In America, and her client list included major corporations like American Airlines, DuPont and IBM. But just as important to her success was her insistence on professionalism in both her work and appearance. First with her bosses at Time, Inc. and later with the executives of large corporations, Bergson worked hard to be taken seriously and to present ideas whose evident quality would speak for them. The office environment, especially when she began her career in the ‘40s, has often been referred to as “a man’s world”, but Maria Bergson made it her own.

Next Post: Jacob Lawrence, artist and chronicler of the Great Migration.