One of the most striking ways in which past eras have differed from our own is the average person’s experience of childhood. Today in the United States most of us consider it a basic entitlement for a child to have continuous schooling for twelve years, while a century ago many children had no guarantee that they would receive any official education at all. Today we consider that no child under the age of fourteen should be made to work, but in the early 20th century children from poor families worked at shockingly young ages, facing utter destitution if they didn’t. It is only relatively recently that a firm line has been drawn between childhood and adulthood, with children spending their time in study and play while adults work to support them; before that line was drawn, many children in underprivileged circumstances found that they had to be the adults of the family.

Phoebe Ann Moses was one such child. Born in Darke County, Ohio in 1860, she was part of a large family thrown into desperate poverty by the loss of her father in 1866. Moses had followed her father on hunting trips as a little girl, and at the age of seven she was compelled to follow in his footsteps, trapping and shooting game as well as selling it to grocers in Greenville. Though her mother and siblings also worked, she was the breadwinner of the family; it was principally her earnings that allowed the mortgage on the family house to be paid off when she was about 15 years old.

Though the dark, freezing woods were no place for a young child, Moses was menaced more by other people than by wild animals. At the age of nine, while staying at the Darke County Infirmary, she responded to a request posted by a local couple for an older child to take care of their infant son for fifty cents a week. When she arrived at their house, Moses discovered that the couple actually expected her to do all the household chores and that they were demanding taskmasters. In her autobiography she later called this couple “the wolves,” and their actions certainly seem to justify the label: they beat her, refused to let her return home, and wrote fake notes to her mother pretending that she was well treated and receiving an education. In the end she escaped from the couple and was able to find refuge at the home of a family friend, but the abuse she suffered left a permanent mark on her.

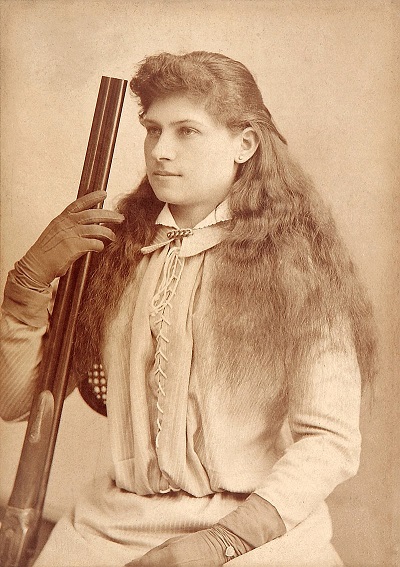

In her teens, Phoebe Ann Moses occupied an unusual position in her community. Only five feet tall, and a woman, she was nonetheless renowned as one of the greatest sharpshooters in southwest Ohio. At one point she was even invited by Jack Frost, a hotel owner in Cincinnati who served her game in his restaurant, to enter a competition against professional rifleman Frank Butler. She entered under the name of “Annie” and shocked Butler by shooting a perfect score of 25 to his 24. He wasn’t just impressed, he was in love, and the two were married a year later.

Living with Butler around Cincinnati, where they performed together as sharpshooters, Phoebe Ann Moses adopted for the first time the pseudonym under which she would become nationally famous: Annie Oakley.

Oakley and Butler would both become stars of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show starting in 1885, and her fame soon spread nationwide. She performed for royalty, supposedly shooting the ashes off Kaiser Wilhelm’s cigarette at his request and even appeared in a Kinetoscope movie produced by Thomas Edison to demonstrate her skills. Oakley’s tricks with a gun seemed endless: she would shoot over her shoulder using a mirror, cut a playing card in half mid-air, snuff a candle flame with a bullet and take the corks off bottles in one shot.

Yet Oakley was more than just a skilled practitioner of her discipline. She was also a strong-willed and independent woman who encouraged other women to improve themselves and participate in public affairs. At the turn of the 20th century she wrote a letter to President Roosevelt offering the services of 50 “lady sharpshooters,” as she put it, to serve in the Spanish-American war. Her activities in civilian life were even more extraordinary; it’s estimated that she personally trained at least 15,000 women how to use a gun, considering the practice both good exercise and a means of self-defense. In her words, she wanted “to see every woman know how to handle guns as naturally as they know how to handle babies.”

Late in her life Oakley remained a philanthropist, a champion of women’s causes, and a record-setting sharpshooter. She participated in shooting contests well into her sixties and ultimately became both a pillar of her community and a national symbol of female empowerment. Oakley seemed to have an inner strength that came not just from her competence and skill, but from having endured great adversity at a young age. A clue to this may be found in her autobiography, which mentions that she was sometimes asked why she spent so much on charity and so little on herself. This was her response:

“If I spend one dollar foolishly I see the tear-stained faces of little children beaten as I was”

Next Post: Randy Shilts, the noted gay author and journalist who frankly but sympathetically addressed the AIDS epidemic in America.