It’s a sad irony of life that many people who spend their careers making others laugh have little to laugh about themselves. In recent decades many comedians have publicly discussed their struggles with depression, but the relationship between professional humor and private sorrow has been a topic of art and literature for centuries. The subject even inspired one of history’s greatest operas: Pagliacci, the story of a clown who suffers in real life the same mockery and humiliation that his character endures on stage to amuse the audience. Our own lives are rarely this tragic, yet many of us can recall times when we had to perform at our best despite our own emotional stress.

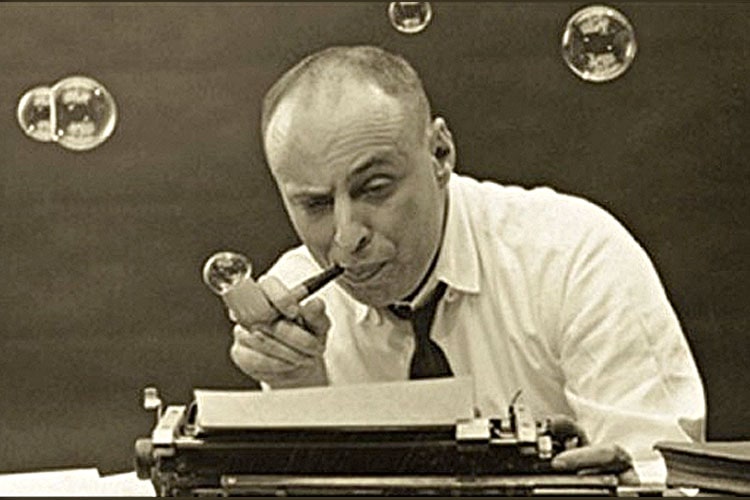

The best comedians are able to take the pain and stress of the world they experience and find the humor in it, causing their audiences to look at life in a new way. Their humor can be satirical, aimed at society’s vices and mistakes with the hope of making the world a better place, or it can simply aim to give the audience a few moments of happiness. These are both worthy pursuits, and the founder of Mad magazine was an expert at both of them.

Harvey Kurtzman was born in a Brooklyn tenement on October 3, 1924. His parents were Ukrainian Jews who had fled their home city of Odessa several years before during the aftermath of the Russian Revolution. Four years later his father died of a perforated ulcer, and his mother, in desperate financial circumstances, placed him and his older brother in an orphanage for several months. She finally found work as a milliner and was able to retrieve them, and soon after she remarried. The family settled down to a more or less normal life, but throughout Kurtzman’s childhood they were always poor.

Even as a child Kurtzman was drawn to the visual arts. He made elaborate chalk drawings on the sidewalks of his neighborhood, attracting the attention of passersby who would stand and watch him work. Reading comics was one of his favorite hobbies, but because his parents read mostly political newspapers he had few opportunities to read them at home. Eager for more reading material, he would go through his neighbors’ garbage cans and pick out the Sunday comic sections of their discarded newspapers. By his mid-teens he was a cartoon aficionado, having entered and won several contests with his own work, and after graduating early from high school in 1941 he decided to turn his passion into a career.

His early experience with the comic industry, however, was far from encouraging. After a meeting with Alfred Andriola, creator of the detective comic Kerry Drake, the teenage Kurtzman was told that he ought to give up on cartooning. Dismissing the older cartoonist’s advice, he worked a series of odd jobs until finally, when the year was almost over, he found a position as an assistant at the studio of Louis Ferstadt. The new job didn’t last long, as in 1943 Kurtzman was drafted into the military, though he never saw combat overseas. Instead he was called upon to illustrate instruction manuals and posters for the U.S. Army, and during this time he continued to submit cartoons to periodicals in the various states where he was stationed.

Fresh out of the Army in 1945, Kurtzman found the comics industry just as hard to crack as it had been three years before. When he applied for a job at the newspaper PM, he faced rejection at the hands of another industry veteran. This time it was Walt Kelly, the Disney animator and creator of Pogo, who told Kurtzman that his cartoons weren’t good enough. For the next several years he struggled to find regular work in comics, supporting himself by freelancing for many different publications, creating crosswords and writing children’s books.

The turning point for Kurtzman came when he encountered William Gaines, the publisher of Entertaining Comics, in 1950. At first he was hired by EC only as a small-time freelancer, but when Kurtzman shared his ideas for a new adventure comic book, Gaines hired him on to make them a reality. Rejecting the glossy idealism of most contemporary adventure comics, Kurtzman’s Two-Fisted Tales were gritty and realistic, often based on true stories that he had researched at the New York Public Library. The publication was a success, and many inside and outside EC Comics appreciated its quality, but Kurtzman was still unsatisfied. Because of his perfectionistic approach to writing, and the fact that EC paid by the page instead of giving regular salaries, he was struggling financially and felt underappreciated by his employer. It was Gaines who came up with an idea to change this state of affairs, suggesting that Kurtzman should work on something that would take less time and be easier to produce in volume: a humor comic.

In August of 1952, EC published the first issue of Kurtzman’s new magazine, Mad. Its success wasn’t quite instant, but it was close; by the fourth issue, the new humor comic was selling out on newsstands. Mad took Kurtzman’s usual laser focus on specific issues and applied it to humor, lampooning targets in the movies, the news, and especially the comic industry itself. This approach landed him and his publisher in hot water several times, such as when he parodied the popular comic superheroes Superman and Batman, but Kurtzman and Gaines were adamant about their legal right to mock anything that was mockable. Mad persevered through the legal challenges, and ultimately it became EC’s flagship publication as changing tastes in the comic industry undermined its older adventure and detective comics.

Kurtzman continued to be the leading influence on Mad until 1956, when a dispute with Gaines over control of the magazine led to his departure. He wasn’t done with comics, however, and through the late ‘50s he created several magazines like Humbug and Help! that kept his unique brand of humor in the public eye. He also employed and mentored American cartoonists who later became famous in their own right, such as Terry Gilliam and Robert Crumb. By the mid-‘60s Kurtzman had become exactly the kind of person that he had tried unsuccessfully to impress in his youth, an “elder statesmen” of the cartoon world.

Harvey Kurtzman was an artist who succeeded not because his talent was immediately recognized and rewarded by supportive patrons, but because of his own doggedness in promoting his work and improving his skills. Nearly a decade passed between the time when he entered his chosen field and the moment when he first got regular work in it. He was sustained through this difficult period by his love of comics and his conviction that his work was worth people’s attention, and his eventual success with Mad proved that he was right to value himself highly. The story of his career stands as proof of something else, too: that success in any business isn’t about having connections, it’s about making connections.

Next Post: Norman Borlaug, the agronomist and architect of the “Green Revolution” that rescued millions from starvation.