The pursuit of higher education is one of those personal milestones, like owning a house and becoming financially independent, that has traditionally been associated with the good life in America. Over the last century, going to college essentially replaced the earlier goals of owning land and starting a small business to become the core of the fabled “American Dream”. However, that dream has never been easy to realize for most, especially for those who face barriers to success in the form of legal and social prejudice.

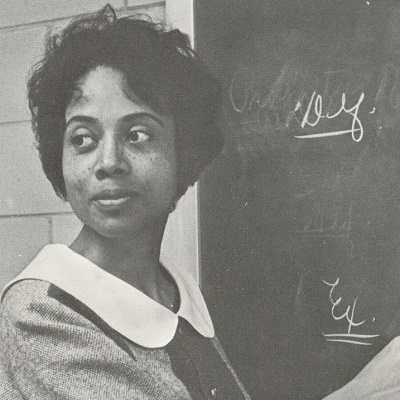

It’s remarkable, then, that many minority students in our country’s history have not only made their way into the university, but have excelled there beyond anyone’s expectations. Some went on to distinguished careers at private companies. Others became influential writers, artists, intellectuals and politicians. But it takes a special kind of public-spiritedness to take the education that one has fought for and reinvest it into the educational system itself by becoming a teacher. In Vivienne Malone-Mayes’ case, this meant sharing her hard-won knowledge even with the institutions that had once stood in her way.

Vivienne Lucille Malone was born in Waco, Texas on February 10, 1932. Both of her parents had worked as schoolteachers, and they had high hopes for their daughter’s education, even enrolling her in school a year early. Vivienne was a model student, and after graduating from her segregated high school in 1948 she immediately applied to Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. Her college experience acquainted her with many hard-working academics, including her teacher Evelyn Boyd Granville, who had recently become the second African-American woman in history to earn a PhD in mathematics. Inspired by her example, Vivienne would ultimately decide to seek a PhD herself.

First, however, she put her already considerable mathematical knowledge to work, chairing the Mathematics department at the historically black Paul Quinn College in Dallas for seven years, and then spending a year in the same position at Bishop College in Dallas. Now, with both academic training and practical experience under her belt, Vivienne was prepared to continue her studies. She applied to Baylor University, a private institution in Waco, but was rejected because of her race. Disillusioned at the time, she later realized that this setback was a blessing in disguise; Baylor did not offer a PhD program, and her studies there would likely not have led to a degree. Instead she applied to the University of Texas, a public institution that had recently been integrated by Federal law, and was accepted.

Once she arrived on campus, however, it became clear how superficial the effects of legal integration really were. The only black person and only woman in many of her classes, Vivienne was isolated in a student body full of people who refused even to speak with her. Despite her eight years of teaching experience, she found herself unable to obtain a teaching assistantship to help her with educational expenses, and she also learned that many unofficial student meetings were held at an off-campus coffee shop that was still segregated under Texas law. Adding to her frustrations, one of the school’s prominent math professors, Robert Lee Moore, flagrantly defied the integration order and refused to allow black students into his classes. The school had been required to admit her, but despite her qualifications she was never allowed to feel that she belonged there.

Vivienne persevered in the face of these legal and extralegal obstacles, gaining her doctoral degree, only the fifth ever awarded to an African-American woman, in 1966. Her experience of injustice on campus had made her an ardent advocate of civil rights, and she marched in numerous protests throughout her life to overcome the persistent legacy of prejudice. Later in life she recalled that one of her professors in graduate school had disparaged civil rights protestors, claiming that if all African-Americans had been diligent students like Vivienne there would be no race problem in America; Vivienne answered back that without the influence of the protestors, her professor would never have met her at all.

However, she never allowed her opposition to racism to become bitter or hateful. In fact, shortly after obtaining her doctorate, Vivienne joined the faculty at the newly integrated Baylor University, the same institution that had refused to accept her as a student, becoming its first African-American professor. Her natural flair for teaching mathematics to all kinds of students shone at Baylor, where she was voted “Most Outstanding Faculty Member of the Year” in 1971, and where she would spend the rest of her career as a researcher and educator. Legal integration had given her a foothold in the world of academia, and with talent and hard work she had built it into her life’s pursuit.

The story of Vivienne Malone-Mayes is a perfect example of the kind of opportunity that many people miss due to prejudice. Practically everyone who met her admired her knowledge and determination, benefiting from the differences that she displayed. The only people who never had that opportunity are the ones who refused to see her in the first place, who allowed race prejudice to blind them to the potential of others. As she once suggested to her professor, if you want to have bright people in your class, you have to meet them first.

Next Post: Elizabeth Cochran, the young girl whose fiery response to a sexist editorial in a Pittsburgh newspaper ultimately led her to a brilliant career as an investigative journalist under the pen name “Nellie Bly”.