For about a century of American history, starting in the 1840s, the only medium of news and entertainment that was truly nationwide was the magazine. Unlike books, which were often too expensive to be accessible, and newspapers, which were generally circulated only within their own hometown, publications like The Saturday Evening Post and Godey’s Lady’s Book reached into hundreds of thousands of homes across the country with news stories, serialized works of fiction, and opinion pieces discussing the burning issues of the day. Readers turned to their favorite magazine for many things that we now tend to get from television or the Internet: information about what’s going on in the world around us, the latest trends in fashion and society, or just a few moments of much-needed diversion.

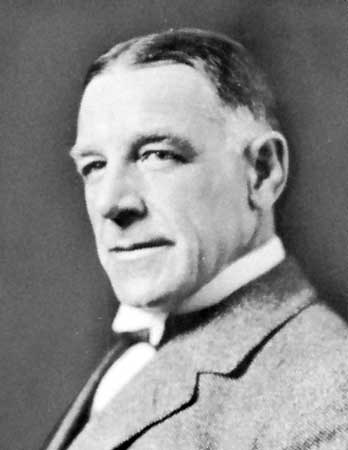

It is generally conceded that the periodical which led the field at the turn of the last century, both in circulation figures and social importance, was The Ladies’ Home Journal, then a monthly magazine published in Philadelphia. The Journal benefited from being located in one of America’s largest cities, as well as belonging to the same prestigious publisher as The Saturday Evening Post, but its greatest assets were the wide-ranging interests and intellectual zeal of its editor, a young and ambitious Dutch immigrant named Edward William Bok.

Edward Bok was born in Den Helder, a coastal city in the Netherlands, on October 8, 1963. When he was six years old his family moved to Brooklyn, where like many immigrant families they faced a steep uphill climb to prosperity. In his autobiography, Bok recounted childhood experiences of washing a bakery’s windows after school and following the tracks of coal wagons to pick up the bits of coal that fell from them. His father had put considerable stock in education, enrolling his sons in school even before they had learned English, but sadly young Edward was to be torn from his studies while he was still in elementary school.

At the age of thirteen Bok dropped out to help support his family by taking a job as an office boy with the Western Union Telegraph Company. His real passion, however, was always writing, and over the next half a decade he gradually worked his way into the publishing industry. Managing to get a job as a stenographer with Henry Holt and Company, Bok spent his spare time writing articles which he eventually sold to more than a hundred newspapers as a syndicated column, known as the “Bok Page”. By his mid-20s Bok was already making a mark in the publishing world as the co-owner (with his brother) of a private press, editor of several small magazines, and advertising manager for the popular Scribner’s Magazine.

As it happened, many advertisements for Scribner publications were placed in The Ladies’ Home Journal, already one of the leading women’s magazines of its time. Through this connection, and the success of his syndicated column, Bok came to the attention of the Journal’s publisher, media magnate Cyrus Curtis. Curtis was impressed by the young man’s dynamic attitude, and when his wife Louisa retired from editing the magazine in 1889, he asked Bok to step in as its new editor. Against the advice of his business associates, who warned him that leaving New York and his established successes behind would ruin his career, Bok took the job.

Although his popular column had focused on a female audience, this new job running a woman’s magazine wasn’t an obvious fit for the austere, socially awkward Bok. He had very little personal experience with women and women’s issues; in fact, as he later confessed in his autobiography, he had never even had a girlfriend. What he did know well, however, were the problems and hard choices that often confronted those who had a home to manage. As he put it, he chose to aim his magazine at the home his reader lived in rather than the reader herself. Under his leadership, The Ladies’ Home Journal became an all-purpose repository of advice for the busy homemaker, and within a few years Bok’s taste in content and style was validated as the Journal’s circulation figures soared.

Bok also used his editorial position to promote a change in domestic attitudes that he thought was sorely needed in America. An avid reader of Emerson, Bok felt that materialism and an obsession with status were tearing apart the American home, and that simplicity was the solution to this turmoil. Instead of the old-fashioned term “parlor”, Bok for the first time referred to this part of the house as a “living room”, suggesting that this should be a place for family members to enjoy each other’s company, instead of a stuffy and over-decorated shrine reserved for guests. Bok was also a proponent of suburban living, seeing it as a refuge from the clutter and ugliness of the city, and so in 1895 he began publishing plans for simple, inexpensive houses that parents of growing families could build themselves on small plots of land. Professional architects were openly dismissive of these mass-produced house plans, but among the middle-class readers of the Journal they were enormously popular, much like the Craftsman house plans published around the same time by Gustav Stickley.

Bok’s most radical and enduring innovation, however, was something he chose not to do. In 1892, he caused a sensation by announcing that the Ladies’ Home Journal would no longer run advertisements for patent medicines. These quack remedies, many of them containing harmful drugs like morphine and cocaine, were a common sight throughout the 19th century, and most magazines were willing to share in the enormous profits generated by this unsavory industry. Bok had been an advertising man himself, and he was disgusted by the unwarranted claims and deceptive language that patent medicine advertisements were full of. In addition to refusing to sponsor them, he also ran many articles in the Journal discrediting patent medicines, discussing the dangers of their influence on society, and exposing the lies by which they were sold to the public. By the early 1920s, when Bok retired from the Journal, many other magazines had followed his lead, and the golden age of the snake-oil salesman was over.

In his championing of progressive causes, his ethic of simplicity, and the importance he attached to family togetherness, Edward Bok stands out as a strikingly modern figure, a man ahead of his time. Many of his contemporaries spent their whole lives expanding their fortunes and died “in the harness”, still working in their old age; Bok instead chose to retire early and dedicate much of his later life to his family and philanthropic causes. His career was driven by an idea of the good life which he shared with millions of readers, and which at one point resonated so strongly that it made the Ladies’ Home Journal the most popular magazine in the world. In our own time the idea of tasteful simplicity is a familiar one, but in Bok’s time, it was truly revolutionary.

Next Post: Julia Morgan, the student who raced against time and academic discrimination to become the first feamle architect to graduate from the renowned École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.