When we consider the visible Elements of Individuality that lead us to either respect others and take them seriously, or disregard them and their ideas, one that often goes overlooked is age, both apparent and real. In modern American society, as in most societies through the ages, seniority is a powerful indicator of social status. It is taken for granted, though often with good reason, that as they grow older people gain the wisdom and experience that makes them fit to lead others, and consequently the typical person entrusted with the control of an organization will be someone in late middle age. Those who occupy similar positions at a different age are frequently stereotyped as unfit to hold their jobs; younger leaders are assumed to be foolish and immature, while those past middle age face accusations of senility or being “out of touch.”

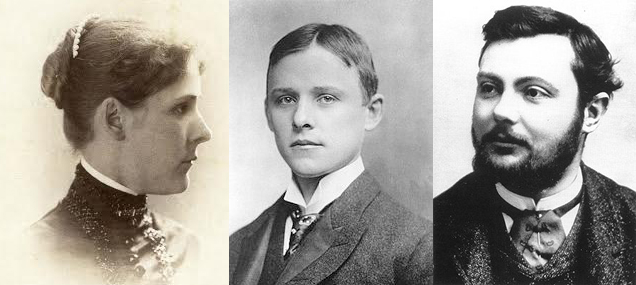

However, it is not just in our current business environment that such stereotypes have been defied by young, ambitious businesspeople. Back in the late 19th century, one of the co-founders of future industrial giant Alcoa was hardly out of college when he discovered a process that would eventually transform aluminum from a costly luxury into an everyday staple. Charles Hall lacked the connections of a seasoned businessman, nor did he possess the clout of a distinguished chemist; he was too young to have acquired either of them. But with his family’s support behind him, particularly the assistance of his older sister Julia, he founded a metallurgical empire. And by a strange coincidence his greatest rival, a French scientist and inventor who discovered the same process independently and almost simultaneously, was the same age as well.

Charles Martin Hall was born on Dec. 6, 1863 in Thompson, a small town in the northeast corner of Ohio. His parents had just returned to their native state after ten years of missionary work in Jamaica, where most of Charles’ siblings had been born, including his older sister Julia Brainerd Hall in 1859. He was a gifted student, and after the family moved to Oberlin in 1873, he began preparing for a college education at Oberlin College, his parents’ alma mater. Finally, in 1880, the 16-year old boy was ready to enroll.

Hall had a strong affinity for chemistry, and in his second term he attended a particularly interesting lecture by noted chemist Frank Fanning Jewett. Jewett showed his audience a sample of pure aluminum, at that time a substance rarer and more expensive than gold and noted that a cheaper method of isolating the metal would greatly enrich both its inventor and the world at large. Hall was inspired; for the rest of his college years and beyond, he spent much of his leisure time under Jewett’s mentorship trying to devise an economical method of obtaining pure aluminum from its naturally abundant ores.

Hall’s first several attempts, such as electrolyzing aluminum fluoride in water, had no more success than the numerous prior experiments made by others. The frustration of these failures was compounded in 1885 by the loss of his mother, but under Julia’s stewardship the family soldiered on. Finally, in 1886, he hit upon an ingenious but simple method that worked: passing an electrical current through a solution of aluminum oxide dissolved in the mineral cryolite, which left a pure precipitate of aluminum at the bottom of the vessel. Julia was there to witness and record the discovery, a fact that was soon to prove vital, for Charles Hall was not the only inventor to discover this revolutionary method. On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, the French scientist Paul Héroult was also busily at work.

Paul Héroult had been born on April 10, 1863 in Calvados, a region of Normandy. His inspiration for seeking a cheaper way to produce aluminum was a treatise on the metal that he had read at the age of 15. Driven and brilliant, Héroult had worked on the aluminum problem for years before reaching the same conclusions as Hall. Both moved quickly to patent their work, so much so that all the major steps were taken in a period of less than six months:

- In February of 1886, Charles Hall demonstrated the process for his family.

- By April, Héroult was ready to file a French patent for the process.

- A month later, in May, Héroult filed an American patent.

- Finally, in July, Hall applied for an American patent, unaware that Héroult had already put through his own application.

Hall ultimately triumphed in the U.S. patent courts, largely because Julia’s records and his own postmarked letters to family members established that he had discovered the process before Héroult claimed he had. Buoyed by this success, he looked for commercial partners in Ohio to work with, but none were forthcoming. Undeterred, Hall went to Pittsburgh, where he joined forces with Alfred Hunt to start what would become the Aluminum Company of America in 1888, later known as Alcoa.

Although Hall was already set for life, and Héroult had been thwarted in his hopes for an American patent, neither was finished with inventing. Hall continued to refine the aluminum-reduction process throughout his life, garnering several more patents in the process. Héroult’s later career was even more distinguished; he developed the first commercially successful electric arc furnace to be used in steel smelting and became a prominent consultant to U.S. Steel, the largest corporation in the world. Neither man bore a grudge against the other, and in later life they treated each other as colleagues. As if in recognition of their cordial rivalry, their discovery is now generally known as the Hall-Héroult process.

One question that always emerges in the stories of great inventors is that of motivation — how inventors find the impetus to carry on despite setbacks and doubt. In this case, the two motivations are very different. Héroult, the lively loner, was kept going principally by his love of the work and by sudden inspiration. Hall, by contrast, was sustained in large part by the support of his unusually close family, with whom he continued to correspond for the rest of his life. His older sister Julia is known to have extensively annotated his letters and research papers; whether this was done during his life in collaboration with him, or after his death as preparation for a biography, is not known, but in either case her critical role in promoting and preserving his experiments cannot be denied.

All three of these people were under the age of 30 when they did their greatest work. They did not occupy university chairs, corporate boards, or public offices, yet from small workshops in private houses they changed the world. It is thanks to their dedication and astuteness that modern aircraft are light enough to fly, that cans and metal foil are made from something stronger than tin, and that many common consumer products endure years of use without rusting into obsolescence. And if the rest of us are willing to support talent and dedication, regardless of where it comes from, there will be many more stories like theirs to come.

Next Post: Maria Callas, the “ugly duckling” of a dysfunctional immigrant family who succeeded, despite personal and professional disparagement, in becoming one of America’s greatest operatic sopranos.