One of the most unfortunate effects of prejudice is that it blinds us to the potential of new discoveries that come from unexpected places. When we insist on sticking to our old ways, associating only with people whom we already know and like, and using tools that are familiar and comfortable to use, we cut ourselves off from the benefits that new practices, new partnerships and new technologies can bring us. At Inclusity we advocate for increased diversity and inclusion in the workplace because we know that it helps businesses to notice and adopt useful innovations; with many different cultures and approaches represented, it’s less likely that the potential contributions of one culture will be ignored because of the prejudice of another.

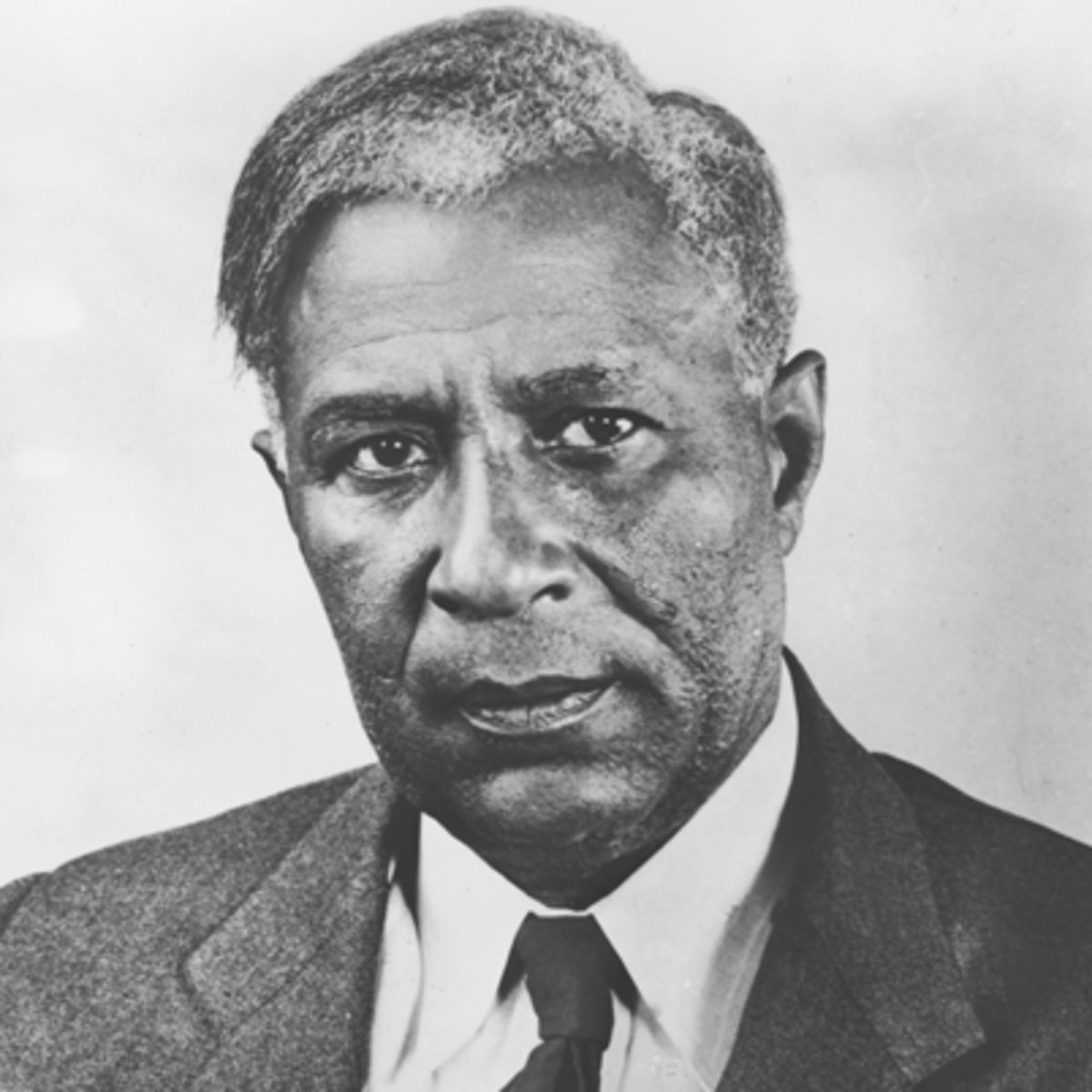

For an invention that could improve people’s lives to be rejected because of prejudice toward the inventor is terrible enough. When that invention is something that could save lives, the consequences of rejecting it are disastrous. But this is the possibility that confronted Garrett Morgan, an African-American inventor who developed a revolutionary smoke hood, then spent years struggling to promote it among customers who cared more about the race of the inventor than the benefits promised by his invention.

Garrett Morgan was born on March 4, 1877, on the outskirts of Paris, Kentucky. His parents were freed slaves of mixed-race heritage, both children of white fathers; in fact, Morgan’s paternal grandfather was the infamous Confederate general John Hunt Morgan. Like many black children of his time, he was forced by economic necessity to leave school early, and with only a sixth-grade education made his way to Cincinnati at the age of 14 to earn a living for himself.

In 1895, after several years of unskilled employment, Morgan was able to find a job as a sewing machine repairman with a firm in Cleveland. There he began to invent and patent parts for sewing machines, which allowed him to save up enough money to open his own repair shop in 1907. This business earned him a modest livelihood, but his first real breakthrough came when, in the process of inventing a chemical to reduce the friction of sewing-machine needles on cloth, he discovered that one of his formulations was able to straighten fabric and hair. Morgan started a company to mass-produce his formula, which he marketed as a hair-straightening cream to runaway success.

With the revenue he made from hair products, Morgan could easily have retired before the age of 30. Instead he continued to invent, and his next discovery was destined to be his greatest: a smoke hood with two tubes, one lined with wet sponge to draw in cool, breathable air from ground level without letting in smoke and dust, the other allowing exhaled breath to escape. A forerunner of the ubiquitous gas mask used during World War I, Morgan’s “breathing device” was a major innovation, and he hurried to market it to fire departments in cities across the United States.

There was just one problem: many of his potential customers had no interest in buying anything, not even a life-saving device, from a black man. To get across the benefits of his invention, he eventually decided to hire a white man to stand by him and promote the smoke hood, pretending to be its inventor. Meanwhile Morgan himself gave live demonstrations of the hood, standing for 15 minutes at a stretch in a tent filled with smoke and noxious fumes, then emerging triumphantly unharmed. However, even in the role of a stuntman, Morgan refused to let on that he was African-American; instead he posed as a full-blooded Native American, “Big Chief” Morgan, fearing that racial prejudice would cause the public to reject his smoke hood unless he kept his own ethnicity a secret.

Morgan’s fears were justified. Although the smoke hood sold well, thanks to its simple but inspired design and his own marketing skill, many customers cancelled their orders when they found out that it had been invented by a black man. Even after he used the hood to personally rescue several men from a collapsed tunnel in 1916, risking his own life and damaging his health to save the lives of others, he was given little credit for his own heroism or the effectiveness of his invention. On the contrary, publicity from the event made it even more widely known that he was black, damaging his sales further.

However, although recognition was slow in coming, it did come eventually. A year after the tunnel collapse, a group of Cleveland citizens presented him with a medal for his role in the rescue. The smoke hood itself won a gold medal from the International Association of Fire Chiefs, and its sales to fire departments across America were brisk. Morgan’s inventive brilliance was praised by the likes of John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan, and he continued to put it to use in products like the first three-way traffic signal in the United States, which he patented in 1923.

The United States is a nation of pioneers, businesspeople and inventors, and there are few people who represent it so nobly as Garrett Morgan, a pioneering inventor and entrepreneur who saw useful innovations where others saw nothing at all. He spent his life making other people’s lives safer, despite scorn and indifference from those who couldn’t see past the color of his skin. Above all, he was a magnanimous man who worked to make the world a better place for everyone, no matter whether they were black or white, near or far, fair-minded or prejudiced.

Next Post: A retrospective on the first year of “From Adversity to Achievement”, and plans for the series’ future.