As a branch of the liberal arts, logic often gets short shrift from the general public. Few university students take classes in logic unless they’re required to. Popular culture mostly ignores it, preferring to draw inspiration from broader fields like physics and psychology. Although formal logic has a history that goes nearly as far back as philosophy itself, the term “philosopher” suggests a brilliant thinker unraveling the enigmas of the universe, while “logician” conjures up the image of a dry-as-dust bookworm who somehow makes even the simplest concepts confusing.

Much of this repugnance towards logic apparently stems from its close association with higher-level mathematics, which many students find intimidatingly complex. But math wasn’t introduced into logic with the goal of making it more confusing; in fact, it was just the opposite. So-called “Boolean algebra”, a concept best known today for its use in Internet search engines, was originally developed to simplify logic and make its rules clearer. This logic is so simple, in fact, that even a digital logic gate, which only recognizes two “ideas” (open or closed), can understand it. Hundreds of millions of these gates are using Boolean algebra in your computer right now, which is why it’s working, and it’s all thanks to the accomplishments of an obscure English logician who never saw a computer in his life.

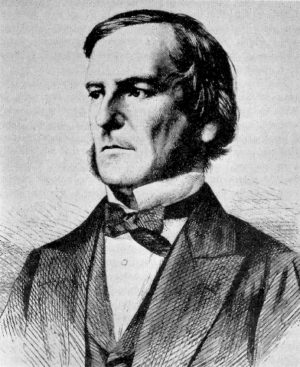

George Boole was born on November 2, 1815 in Lincoln, the county town of Lincolnshire. His father, who worked as a shoemaker, was a lover of science and the liberal arts, and under his tutelage young George became a wide-ranging scholar as well, despite receiving only a primary school education. He had a particular fascination for languages, both modern and ancient. At the age of 14 he penned an English translation of a poem originally written by the ancient Greek author Meleager, which was published in the Lincoln Herald. Soon afterward, one of the paper’s correspondents wrote an indignant letter to the editor claiming that the translation had been plagiarized. The man had no evidence for this accusation other than the self-evident (as far as he was concerned) fact that no 14-year old boy could possibly have written it. This was the first time that one of Boole’s achievements would be dismissed as impossible because of classist bigotry and narrow-mindedness; it would not be the last.

The passion that Boole’s father had for amateur intellectual pursuits did have one rather unfortunate downside: he wasn’t a very good businessman. By the time he was 16 his father’s shoemaking business had nearly collapsed, leaving the burden of supporting the family on his shoulders. Characteristically, he chose to work as a teacher in nearby schools, and a few years later he took the risky and ambitious step of opening his own in Lincoln. At an age when many of us were still attending school, Boole was running one.

Remarkably, Boole was able to make a success of his small day school while also continuing his own education almost entirely outside the academic system. With his thorough knowledge of French, German and Latin he was able to read the works of many great mathematicians in the original, which often did more to help him understand their theories than any university could have done. In 1841 he managed to get one of his papers published in the Cambridge Mathematical Journal, and many other publications followed. By the age of 30 he had already become a prominent mathematician, even receiving a gold medal from the renowned Royal Society for a paper discussing ways to combine the methods of algebra and calculus. However, this accolade didn’t come easily; many of the Society’s members felt that a man with no academic background wasn’t a proper scientist, and the paper had to be submitted twice before its merit was recognized.

Up to this point, Boole had been noted primarily as a mathematician and schoolmaster, not a logician. However, this would all change in 1847, when he published an essay titled “The Mathematical Analysis of Logic”. In the essay he argued that logic, which had traditionally been treated as a branch of philosophy, could be dealt with more effectively if it was considered as a branch of mathematics, particularly by using the methods of algebra. In the process he reduced the possible “values” of logical statements to two numerical alternatives, either 1 (“true”) or 0 (“false”). Although Boole could hardly have known it at the time, his “binary logic” anticipated by a century the technology which benefited most from its existence: the modern digital computer.

The rewards which Boole received for his contributions were, like the man himself, modest. In 1849, he was appointed Professor of Mathematics at Queen’s College in Cork, Ireland. The job came with a salary of £250 a year (equivalent to around £30,000 today), but very little increase in status; he had no assistant and graded all his students’ work himself, just as he had while running his own school. More impressively, in 1857 he was elected to a fellowship in the Royal Society, as one of its few fellows with no university education. The principal reward he received, which mattered to him far more than money or status, was the esteem and kudos of his fellow researchers.

However, Boole was not a monomaniac obsessed with science to the detriment of everything else. He spent a great deal of time on social causes, particularly the promotion of intellectual resources for the working classes. One of his favorite causes was the Mechanics Institute, an educational institution created to educate adult men in technical subjects. On top of his promotion of charitable education, he also campaigned for the reduction of laboring hours in city shops, as well as supporting the pro-democracy Chartist movement in the 1850s. Among the many famous scientific personalities of the 19th century, Boole stands out not as an eccentric genius with a one-track mind, but rather as a true philanthropist in the vein of Andrew Carnegie.

George Boole was a man who brushed right past the class-based barriers that stood in the way of his goals. His early dedication to amateur intellectual pursuits, which would have struck many at the time as a foolish indulgence, became in his hands a way to climb the ladder of success. Despite never attending a university, he became a respected professor at one for many years, as well as a pioneer of thought whose work commanded the attention of those who read it. Back when he was a 14-year old boy publishing poetry in a local paper, it may have been possible to deny his genius; in the middle of his career, there were still some who doubted his credentials; but now, after his theories have produced one of the most transformative technological revolutions in history, he cannot be ignored.

Next Post: Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, the obscure astronomer whose thesis on the elemental composition of the Sun was so revolutionary that established authorities couldn’t (and wouldn’t) believe it.