One of the most difficult tasks that Inclusity’s trainers face on the job is mediating the conflicts that emerge when personalities and cultures clash in the workplace. These conflicts can be aggravated by the fact that many people in the modern workplace were raised to be both fiercely proud of their own native culture and hostile to foreign and unfamiliar ones.

Challenging this attitude in the modern workplace, where many companies recognize the contribution that inclusion makes to their bottom line, is still a slow and challenging task. Imagine, then, how difficult it must have been to advocate tolerance in the middle of a global war, toward those who share a common culture with the enemy that your government spends much of its time heatedly denouncing. This is the monumental task that Isamu Noguchi attempted in the midst of World War II, while more than a hundred thousand Japanese-Americans were being imprisoned for bearing a resemblance to America’s enemies.

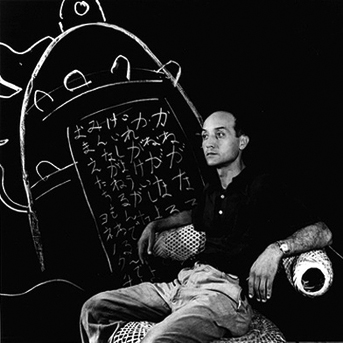

Isamu Noguchi was born on November 17, 1904, to Léonie Gilmour, an American writer who lived in Los Angeles. His father was Yone Noguchi, a Japanese poet who left Gilmour shortly before her son was born. Isamu lived in Tokyo with his mother for most of his childhood, his father never rejoined the family. Yone Noguchi’s one contribution to his son’s development was to give him the name “Isamu”, which means “courage” in Japanese.

At the age of fourteen Isamu was sent back to the United States to be educated at a progressive school in Rolling Hills, Indiana. Under the care of the physician Edward Rumely, he diligently studied and eventually decided that he wanted to be an artist. A brief and disillusioning apprenticeship with the famous sculptor Gutzon Borglum, the creator of Mount Rushmore, eventually led him to enroll as a premedical student at Columbia University. Ironically, though, while his first taste of the art world had pushed him toward medicine, the acquaintances he met at medical school, many of them fellow Japanese-Americans, urged him to go back to art, and with several years of study at the Leonardo da Vinci Art School in New York City, he became a moderately successful sculptor of portrait busts.

Like many artists, Noguchi spent much of his early career travelling around the world and picking up new techniques. In 1927 he spent seven months in Paris as an apprentice to the modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi, an unusual mentor in that he didn’t speak any language that his student understood particularly well (they usually conversed in French, even though Noguchi barely knew any French). Upon his return to New York City, Noguchi experienced even more of the fringes of the art world, including an encounter with the idiosyncratic designer Buckminster Fuller, for whom he made several models of experimental inventions. By the early 1930s he was already a cosmopolite full of strange new ideas for sculpture, and his appreciation of form led him to tackle industrial design projects as well. One of his early projects was the Zenith Radio Nurse, the first commercial baby monitor put on the market in 1938; its smooth lines and soothing appearance are strongly reminiscent of the biomorphic furniture that Noguchi would later design during the 1950s.

However, Noguchi’s personal circumstances would soon be far from soothing. In 1941, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor stirred up a wave of vengeful anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. In February 1942 the country’s president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, issued an executive order authorizing the Secretary of War to designate “military zones” in which residents of Japanese descent would be forced into internment camps for the duration of the war. In the event, the “military zone” that was drawn up included the entire West Coast, where almost all Japanese-Americans lived.

Noguchi was horrified by this prospect, and he joined with other Japanese-Americans in New York to protest the imprisonment of a hundred thousand people who had committed no crime, but their protests fell on deaf ears. Noguchi then attempted to organize support efforts to prove the loyalty of Japanese-American citizens. When this also went nowhere, he finally decided to voluntarily enter a camp in Poston, Arizona and do what he could to improve conditions there.

From the start his plan exposed him to suspicion and resentment on all sides. His fellow internees, unable to believe that any man would willingly subject himself to what had been imposed on them, were certain that he was a spy sent by the camp authorities to implicate them in suspicious activity and justify further repression. The authorities themselves, meanwhile, were irritated at Noguchi’s interference, seeing him as a pest who was getting in the way of their work. Though Noguchi came up with many ideas for leisure facilities at the camp, such as baseball fields and swimming pools, no one who ran the camps had any intention of actually building them, a fact that Noguchi eventually realized to his chagrin after several weeks of thwarted effort.

Seeing that he was not going to be allowed to accomplish anything, Noguchi applied for release only a few months after entering the Poston camp. Now the ugly prejudice and distrust of the authorities became acute. He was labeled a “suspicious person” for having protested the internment back when it started, and the authorities decided to keep him in the camp he had voluntarily entered. When he was finally granted a month-long furlough, he left the camp and never returned. This was used as an excuse to order his deportation, and the FBI openly accused him of espionage. With the intervention of the ACLU, Noguchi was protected from this trumped-up charge, but the experience left him shaken and angry at the treatment he had suffered, and that tens of thousands continued to suffer throughout the war.

Nevertheless, he had survived, and the brightest days of his career were ahead of him. As the 1950s rolled on he created several icons of modern design, including the famous Noguchi table produced by Herman Miller, while also sculpting innovative artworks that would appear in museums around the country, and ultimately the world. Before the war, he was just a typical dilettante sculptor who had spent some time in Paris, but a decade after it he was an American icon and a pioneer of design.

For the rest of his career Noguchi was very tight-lipped about his experiences during the war. He preferred to talk about art, and the way he spoke in interviews suggests that he didn’t spare much thought for himself and his personal grievances. However, reading the letters that he wrote at the time reveals a surprising depth of feeling from a man who often came across as coldly rational and abstracted. He wrote:

“I decided that things being the way they are I might as well dive into one of these relocation settlements to see what I could do to help preserve self-respect and belief in America…I feel we should make clear that we are fighting the enemies of democracy, and not our own citizens who unfortunately have the blood of one of our axis enemies, Japan. I understand that neither Germans nor Italians have been moved (excepting of course known subversive elements)…Maybe they think that race hatred is good for the war spirit. Maybe they are right—it’s very sad.”

Next Post: Antonio Pasin, the cash-strapped cabinetmaker who created that classic of American suburban childhood, the Radio Flyer wagon