Forty years ago, personal computing was a niche hobby for enthusiasts willing to spend hours tinkering with parts, something like building a ham radio kit. Mentioning a “computer” in the business world at that time would conjure up the image of an entire room full of heavy machines and blinking lights. Now most Americans consider a personal computer essential in our business and personal lives. One would think that, because of this massive change, the best-selling personal computer of all time would be a relatively recent one. As it happens, the top two best-selling PC models of all time were released in the 1980s by a company that no longer exists: Commodore International. And the founder of that company was the abrasive, but visionary entrepreneur Jack Tramiel.

Tramiel’s origins were humble, but not at all tranquil. He was born in Lodz, Poland in 1928, and was only five years old when nearby Germany became a dictatorship under the absolute rule of Adolf Hitler. Tramiel wasn’t yet in his teens when Poland fell to the Nazis, and after the ghetto in Lodz was set up he was sent there to work in a garment factory. Soon he and his family were sent to Auschwitz, where he was one of the relatively fortunate inmates declared “able to work” and moved to the Ahlem labor camp. Tramiel and his mother managed to hang on until their camps were liberated; his father, sadly, was one of millions who were killed.

In 1947, two years after he was freed by the U.S. Army, Tramiel immigrated to the United States and joined the army himself. One skill he picked up that would stay with him was repairing office equipment, particularly typewriters. His service also gave him access to a $25,000 loan, which he used in 1953 to open a repair shop in the Bronx. Even the name of his shop reflected his military background; while he found the names “Admiral” and “General” were already taken, he eventually settled on “Commodore Portable Typewriter”.

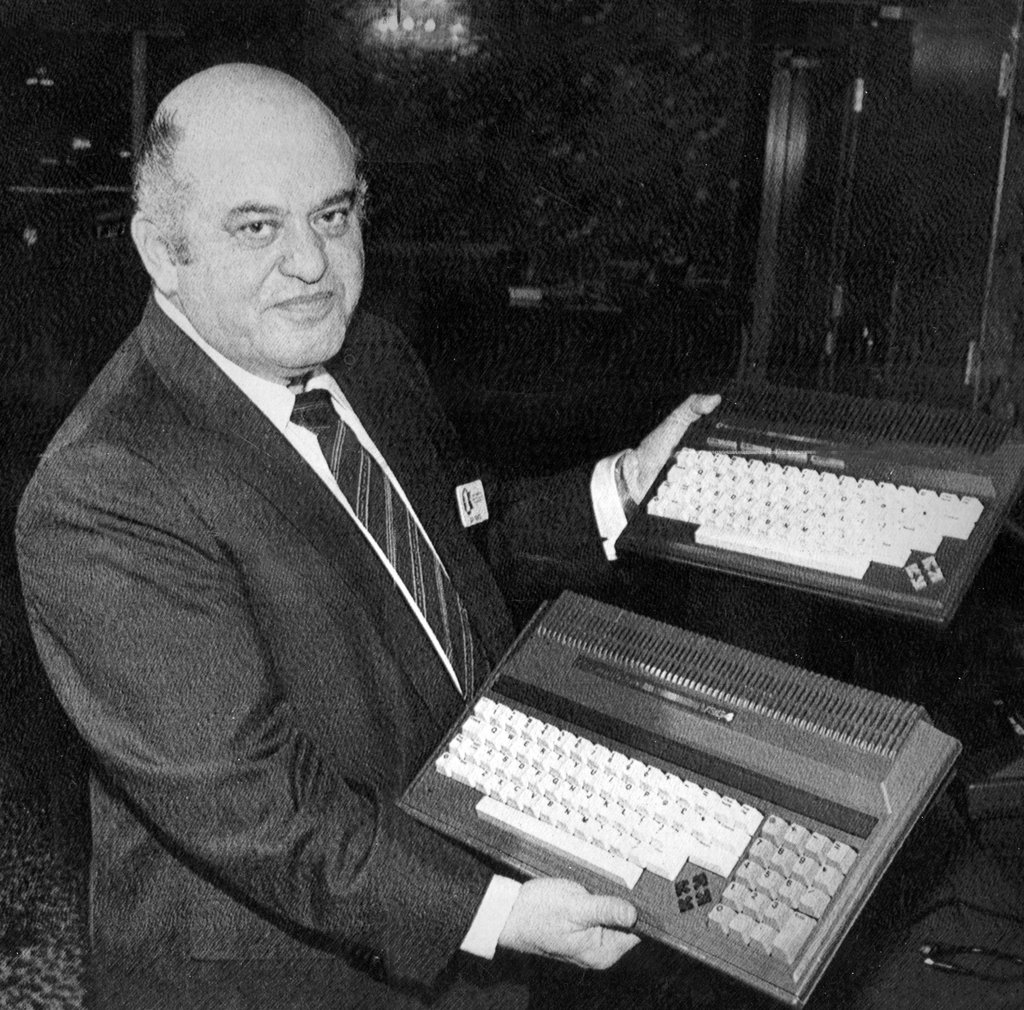

Commodore eventually moved from repair to retail, selling typewriters and calculators throughout the 1960s and early ‘70s. In the mid-‘70s, however, Tramiel was convinced by electrical engineer Chuck Peddle that calculators were a dead-end technology. Peddle recommended that Commodore branch out into home computing, and he worked with them to produce the PET 2001, an all-in-one computer that became a huge success. Later models also sold well, with the VIC-20 being the first computer to sell over a million units, but Tramiel wanted to go even further, and to do that he had to shake up the entire computer industry.

Up to this point computers had been seen as expensive high-tech equipment, useful for schools and interesting to hobbyists but not a product that most consumers would ever want or need. Computers tended to be sold in specialized electronics stores that the average person would never enter. Tramiel now decided that Commodore should focus on “computers for the masses, not the classes”, and the result of that line of thinking was the best-selling Commodore 64.

The secret of the Commodore 64’s success was its focus on accessibility and value for money. The computer was sold in ordinary department stores, toy stores and college bookstores, and it was cheaper than all of its similarly-powered competitors. Tramiel insisted that, despite the low price point, their product needed to have 64 kilobytes of RAM, a tough decision since at the time the necessary chips cost over $100 (out of a total retail price of just $595). Confident that the technology was improving and that chip costs would fall, Tramiel pushed ahead and delivered a value proposition that his competitors couldn’t match.

Jack Tramiel wasn’t a particularly easy man to work with or for. Having founded the company, he treated it in a very proprietary manner, micromanaging projects and insisting on tight control of budgets. He also had a reputation for undervaluing the importance of software design and being tough on dealers who sold his computers. His insistence on a modest price point combined with attractive features made his products popular with consumers, but his methods for accomplishing this feat led to friction within his organization. Ultimately, his investment partner Irving Gould pushed him out over a dispute on how the company should be run.

Tramiel went on to purchase the nearly-defunct Atari, Inc. in 1984 and recreate it as a manufacturer of low-priced computers like the Atari ST. While neither he nor Commodore International were as successful apart as they had been together, both continued to be major players in the computer industry for some time. He also helped to establish the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, which includes a personal tribute from Tramiel to Vernon Tott, the U.S. Army soldier who led the liberation of Ahlem labor camp.

Jack Tramiel was a unique force in the world of computing. Describing himself as a businessman rather than an engineer, he led the creation of world-beating products even as his prickly personality made enemies among both competitors and co-workers. Yet even those who derided his methods had to respect the quality of the products that emerged from them. It is worth noting that, despite the low opinion that many software developers had of Tramiel personally, more than 10,000 software applications were developed for use on the Commodore 64.

Next Post: Paul Revere Williams, a Renaissance man of architecture and home designer for the stars.