“To those of my race who depend on bettering their condition in a foreign land, or who underestimate the importance of preserving friendly relations with the Southern white man who is their next-door neighbor, I would say: ‘Cast down your bucket where you are. Cast it down in making friends in every manly way of the people of all races by whom you are surrounded.’”

This was the advice that Booker T. Washington gave to the African-American public in 1895, a mere 30 years after the end of both the American Civil War and the institution of slavery in the United States. He followed it with a similar exhortation to the white citizens of the South, asking them to work alongside their black neighbors and live with them in peace. Washington assumed that, for better or for worse, the fortunes of African-Americans were bound to the southern states, where about 90% of them still lived at the time of his speech. There they had history and a culture resembling that of the white populace; in any other place, including the northern states, they would be surrounded by strangers and unsupported by tradition and community ties.

Posterity was to learn that Washington had been both too optimistic and not optimistic enough. Racial conflict and discrimination in the South, far from shrinking as black citizens struggled to better their lot, grew and raged out of control. For many African-Americans the South became a prison of debt and legalized oppression, while the North with its great cities and factories seemed more and more like a promised land. Washington’s audience had cast down their buckets, but the water that had come up was too bitter to drink.

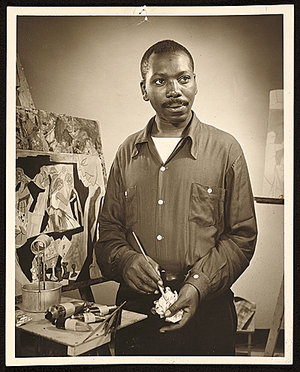

And so, driven from behind by racism and led forward by the prospect of gainful employment, millions of African-Americans moved from Southern farms to Northern cities in what became known as the Great Migration. And no one chronicled that movement more frankly and eloquently than the artist Jacob Lawrence.

Lawrence’s parents had experienced the difficulties of the Great Migration firsthand. They had moved the family from the rural South to Atlantic City shortly before he was born in 1917. Sadly, his family didn’t stay intact for long; his parents divorced when he was seven years old, and the children were placed in foster care. While his mother brought him and his siblings to her new home in Harlem a few years later, his father never returned.

Lawrence ended up drifting, with few prospects except for a pronounced interest in art. It didn’t help that his formative years happened to also be the worst years of the Great Depression. He dropped out of school at the age of 16 and supported himself with odd jobs while he attended classes at the Harlem Art Workshop. Thanks to support from his teachers, particularly the Harlem Renaissance sculptor Augusta Savage, he was able to attend the American Artists School on a scholarship and, more crucially, begin working with the Works Progress Administration. His magnum opus, the Migration Series, was funded by the WPA and shares many stylistic elements with the WPA-sponsored public murals of the 1930s and ‘40s.

The Migration Series comprises 60 panels covering many different aspects of the great migration, most notably its causes, the migrants’ experiences during their journey, the consequences for those who stayed behind, and the reactions of white onlookers. Lawrence used simple, approachable images and captions both realistic and emotional, intertwining matter-of-fact statements (“Many migrants found work in the steel industry”), with more sentimental reflections (“The migrant, whose life had been rural and nurtured by the earth, was now moving to urban life dependent on industrial machinery”).

The overall message of the series is positive, celebrating the strength and adaptability of the migrant, but at the same time Lawrence doesn’t present the North as a paradise or gloss over the difficult aspects of the move. In his panels, white industrial workers assault migrants for lowering factory wages and breaking strikes with their labor; already-wealthy black citizens of the North ignore and snub the poor, shabby newcomers; migrants live in cramped tenements and suffer from disease and violence. As he says in panel 49, there was discrimination in the North, just of a different kind from that the migrants had known in the South.

Lawrence was only 23 when he created the Migration Series, and his career was far from over. After serving in the first racially integrated Coast Guard crew during World War II, he created a War Series in much the same style as his earlier work; series of paintings on historical themes eventually became a major focus of his work. He also taught at several schools, passing on the skills and passion that he had absorbed from the artists of the Harlem Renaissance.

In many ways Lawrence himself demonstrates the fulfillment of those hopes that gave rise to the Great Migration. He was born to parents whose marriage broke apart in less than a decade; Lawrence himself married Gwendolyn Knight in 1941 and formed a bond that lasted almost six decades. His parents were poor and obscure; Lawrence achieved nationwide fame and was the first African-American artist to have his work exhibited in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. He had a difficult upbringing, but ultimately it was his life in the city that provided him with the connections that launched his career: to other artists in Harlem, to the federal government, and to the museums that displayed his work. By moving from the South to the North, his parents gave him the chance to make a better life for himself, and he made the most of that chance.

The last three panels of the Migration Series describe succinctly what the Great Migration ultimately meant to Lawrence and his contemporaries:

“In the North African-Americans had more educational opportunities.”

“In the North they had the freedom to vote.”

“And the migrants kept coming.”

Next Post: Belle Kogan, an industrial designer who challenged the world…and her clients.