Many people can remember a time in their careers when everything seemed to be conspiring against their success, from the tools in their hands to the supervisors watching over their shoulders. We generally tend to get over this feeling after a little while, recognizing that comes it more from stress and frustration than from reality. Few of us could say with assurance that our bosses were actually trying to prevent us from doing our jobs. But for today’s subject, working in the murky atmosphere of World War II military intelligence, this bizarre situation was a reality. The reason is quite simple: she was one of MI5’s most talented intelligence officers, and her boss, Kim Philby, was one of the Soviet Union’s most efficient double agents.

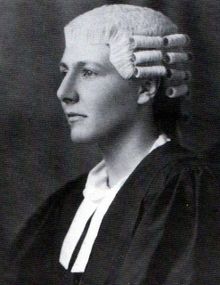

Jane Archer was born in 1898 in Bengal, then part of the British Raj, but grew up with her parents and brother in London. After a distinguished education at Princess Helen’s College in Ealing, she joined the British intelligence service MI5 as a clerk. While working her way up the secretarial ranks she also studied law, eventually being called to the bar in 1924 as one of Britain’s few female barristers. But her real breakthrough was to come in 1929, when her superiors broke precedent and made her MI5’s only female officer, moving her to the investigations and inquiries division and assigning her the job of investigating Soviet intelligence operations. Archer thrived in her new position, developing a formidable talent for interrogation that stood her in good stead when she debriefed the Soviet defector Walter Krivitsky in 1940.

Krivitsky had defected secretly in 1937, shortly after the assassination of his friend Ignace Weiss, who had openly broken with the Soviet cause shortly beforehand. By 1940 he had already made several revelations that shocked the American and British public, including plans for a non-aggression pact between Germany and Russia, and the fact that two Soviet agents were working in the British civil service. Archer made a thorough report of her interview with Krivitsky that ran to 85 pages, but unfortunately his descriptions of the British double agents were vague and evasive. It was only decades afterward that they were identified as members of the Cambridge Five, a close-knit ring of spies that included the man who later became Archer’s boss.

It’s possible that Archer could have unwound this tangle of clues if she had thoroughly followed up the leads she had. Regrettably, she never had the chance; after she openly criticized the newly-appointed director of MI5 for incompetent management, she was dismissed from her position. For much of the war she worked instead at the SIS studying Irish political activity. Then, in 1944, a new opportunity opened up for her in the Soviet counterintelligence division, Section IX. And it was here that she encountered the man who was in many ways her opposite, Kim Philby.

Philby later wrote in his memoirs that he was terrified of Archer, whom he described as the second-best MI5 agent he had ever known. Her talents, as well as her inquisitive and outspoken personality, made her a mortal threat to him, yet it was precisely because she was so talented that he couldn’t turn her down for the job without arousing suspicion. He settled for the next best solution: restricting the scope of her job and assigning her to tasks as far away from him as possible. Even after she returned to MI5 near the end of the war, Philby continued to interfere, recommending another agent over her in 1945 to debrief the recently-defected Soviet cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko.

Despite all his precautions, however, Philby was ultimately unable to keep the thin stream of clues leading to him from becoming a flood. After the United States shared findings from its Venona decryption project with MI5, the identity of a member of the Cambridge Five was uncovered: Donald Maclean, a British diplomat whom Krivitsky had called by the code name Homer. Maclean and another Cambridge Five operative, Guy Burgess, fled to Russia to avoid prosecution, but their careers in espionage were over.

Working with fellow operative Arthur Martin, Archer then uncovered suspicious documents that implicated civil servant John Cairncross as well as Philby himself. The evidence wasn’t strong enough to convict either man of espionage, but Cairncross was forced to resign and Philby was asked to take an early retirement, though the head of SIS still believed in his innocence. The Cambridge Five had managed to compromise British intelligence for more than three decades, but now they had finally been apprehended and removed from their positions of power and influence, thanks in no small part to the dogged efforts of Jane Archer to unmask them.

The reading public has been fascinated by spy stories for more than half a century, but few of those stories are as compellingly intricate as the true story of Jane Archer and her work at MI5. She was a unique figure in her field, a female intelligence agent with a legal background who developed a reputation as a brilliant interrogator. Her accomplishments would be remarkable in any operative, but they are especially so coming from someone whose career was under constant attack, not just from the pettiness of office politics but from outright sabotage by her own superior. And her story suggests that sometimes, even when everything really is against us, we can still achieve great things.

Next Post: Frank Capra, the Italian-American immigrant who overcame a crisis of despair to become one of America’s most inspiring filmmakers.