In 1773 Catherine the Great of Russia placed an order for a 944-piece ceramic dinner and dessert service from an English pottery firm. Ordering new china was something monarchs did all the time, but there was one thing that made this case unusual. Instead of porcelain, the luxurious and desirable material that had dominated royal tables for more than a century, this new service was to be made of earthenware, ordinarily the simplest and cheapest kind of pottery manufactured. However, this was no ordinary earthenware; this was “Queen’s Ware”, a cream-colored material with a brilliant luster that had made it a sensation for the last several years. It was an exceptional product, all the more remarkable for having been invented by a potter who couldn’t throw a single pot himself.

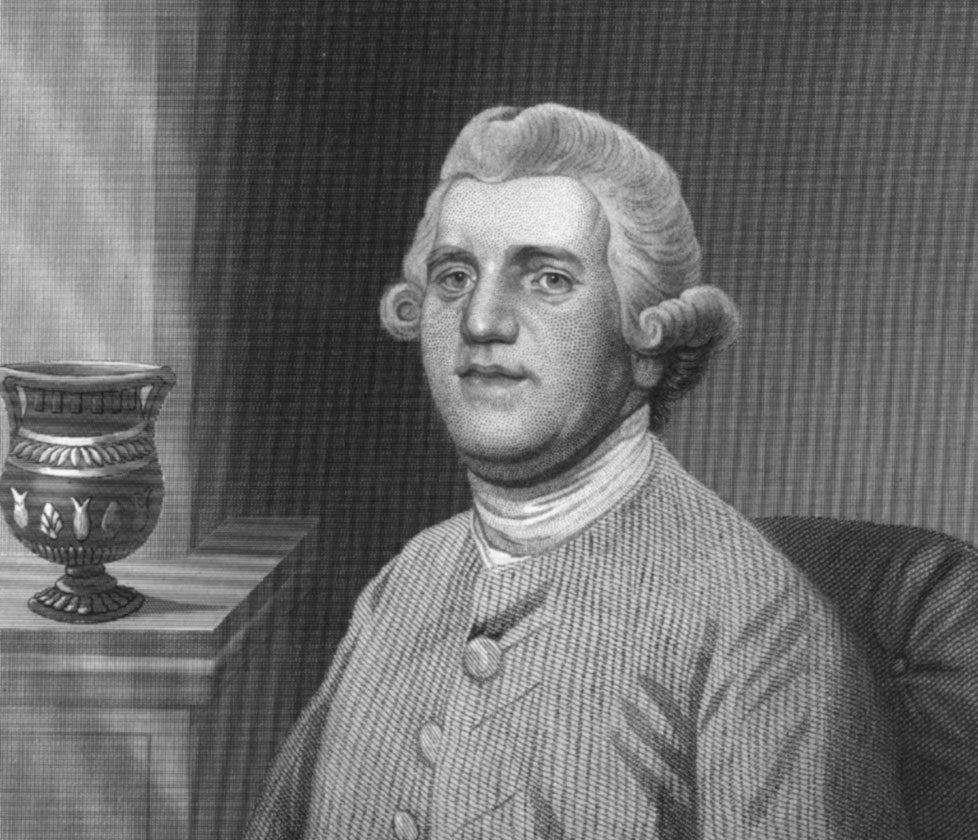

Josiah Wedgwood was born to a family of potters in what is now Stoke-on-Trent, Staffordshire on July 12, 1730. This area, often called “The Potteries”, was already famous for the quality of its ceramics, and it would eventually see the rise of most of England’s great pottery firms, including Minton, Spode and Royal Doulton. Wedgwood began his career as an apprentice potter under his father, and later on his elder brother. The young Josiah showed great promise in forming the cheap, simple earthenware made by his family’s pottery, but just as he was beginning to develop his talents, disaster struck.

In his early teens, Wedgwood suffered a severe bout of smallpox that left him bedridden for more than a year. Worse still, it permanently weakened his right knee, which meant that he couldn’t operate a potter’s wheel. Suddenly the trade he had spent his childhood learning was cut off from him. Wedgwood put this unwanted downtime to good use, reading widely during his illness and researching the latest technological developments among Stoke-on-Trent’s cutting-edge potters. Unfortunately, the knowledge he obtained wasn’t enough to make up for the work he couldn’t perform. His family’s small pottery simply couldn’t afford to employ a “knowledge worker”, and so at the age of 16 he left and sought work elsewhere.

After a series of short jobs at other potteries, Wedgwood formed his first long-term partnership with Thomas Whieldon in 1754. Whieldon, already a successful and influential potter, gave Wedgwood the freedom he needed to experiment with new materials and techniques. It was at this time that Wedgwood began his “experiment book”, a detailed record of his research into chemistry and materials science with the aim of improving ceramics. Finally, after five years of productive experimentation with Whieldon, he decided to strike out on his own in 1759.

Wedgwood’s first major success was the same fine earthenware that would later impress Catherine the Great, an improvement on an earlier kind of Staffordshire pottery called “creamware” that rivalled porcelain in its durability and beauty. A keen marketer as well as a designer, Wedgwood had petitioned the Queen of Great Britain to allow him to call it “Queen’s Ware” after she commissioned a dinner set made from it. She agreed, and soon Wedgwood’s line of ceramics was an international sensation. Later, in the 1770s, he would follow up this success with a line of dark, unglazed pottery, which he called “jasperware” in reference to its gem-like appearance.

Styling wasn’t the only aspect of pottery in which Wedgwood was an innovator. In 1766 he constructed the first modern ceramics factory, where he was able to mass-produce his most popular wares and make them affordable to the newly-emerging middle class of England, making himself a household name in the process. He was a mass-marketer as well as a mass-producer, selling the public on his wares through forward-thinking methods like illustrated catalogues and travelling salesmen; he’s even reputed to be the inventor of the familiar phrase, “Buy one, get one free”.

Wedgwood’s fascination with chemistry and love of history made him many friends among England’s intellectual class. In 1762 he encountered the renowned chemist Joseph Priestley, who would become a lifelong friend and consultant in his pottery experiments. Like Priestley, Wedgwood was to become a member of the Royal Society, in his case for inventing the first pyrometer to test the temperature of his kilns. Also like Priestley, Wedgwood was a prominent abolitionist, and he was responsible for creating one of the cause’s most famous symbols: a ceramic medallion depicting an African slave with his chained hands held up in supplication, beneath which lies a banner reading, “Am I not a man and a brother?” He was also a close friend to the philosopher Erasmus Darwin, so much so that his daughter would later marry Darwin’s son; one of their own children, Wedgwood’s grandson, was the evolutionary theorist Charles Darwin.

Josiah Wedgwood was a man who brought many diverse interests together to create an unconventional, but unquestionably successful career. Unable to do the physical labor that his family had done for generations, he applied his brain to the problem and made himself useful that way. In many ways, Wedgwood made ceramics a modern industry, changing the image of a pottery from a small family business operating out of a house to a large industrial concern producing ceramic wares for tens of thousands of customers across the globe. It’s no surprise that even today the name “Wedgwood” is practically synonymous with English china.

Next Post: Elizabeth Kenny, the “bush nurse” who used innovative treatments to save lives across the world despite receiving no formal medical training.