In many ways the progress of female emancipation can be credited to the efforts of exceptional women in broadening the definition of “women’s work” over the past several centuries. At the time of the Renaissance in Europe, a typical upper-class woman was not expected to work at all, and her education was restricted to ornamental pursuits such as music, dancing and needlework. By the late eighteenth century it was commonly accepted that a woman might study the humanities and be a writer or an artist, but the thought of educating women as men were educated, in the way that the early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft advocated, was ridiculed and dismissed by most men. It was not until the Victorian era that a woman could study a technical subject like engineering and expect to be taken seriously, and even then most women could hardly dream of a life as a businesswoman or an engineer.

One traditionally male role that is often overlooked by chroniclers of women’s history is that of the architect. However, architecture is quite an interesting field in this respect, because despite its close ties to the fine arts, a field in which women have been able to distinguish themselves for close to three centuries, it has also historically been one of the most socially conservative and resistant to the entry of women. The most prestigious architectural college in the world, that of Paris’ School of Fine Arts, did not even accept a female student until close to the turn of the twentieth century, and even then not without controversy. The woman who rose above this controversy, and who defied great odds to become the school’s first female graduate, was a Californian civil engineer named Julia Morgan.

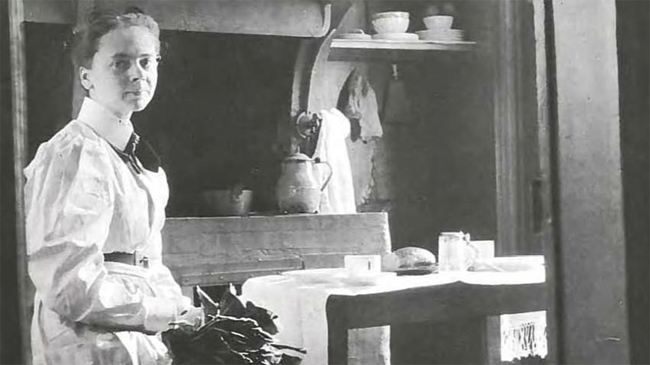

Julia Morgan was born in San Francisco on January 20, 1872. Her family circumstances were unusual for the time because her father, an unsuccessful serial entrepreneur, was not the family’s primary source of income. It was her mother, the heir to a cotton fortune, who exercised a great deal of control over the family finances. Young Julia grew up under the influence of both her mother and her strong-willed grandmother, who moved in with the family after her grandfather passed away in 1880.

Morgan graduated from high school in 1890 with the intention of studying to be an architect, but unfortunately the University of California in nearby Berkeley did not have an architecture program. Instead she studied civil engineering, another male-dominated field in which she was the only female student for most of her classes. She was fortunate, however, to have as a professor the independent-minded architect Bernard Maybeck, who acted as her mentor and encouraged her to complete her studies at Paris’ School of Fine Arts. Maybeck was an inspiration to the young civil engineer, and he would later collaborate with her on two commissions for one of her most important clients: the Hearst family.

As Maybeck had suggested, Morgan travelled to Paris and applied to join the school as an architectural student. But this was a very exclusive program. Hundreds applied to study there every semester, and by tradition only the top 30 were accepted. In October of 1897 she took the entrance exam for the first time, but was only able to rank 42nd and was rejected; it didn’t help that all the exam problems were given in metric units, which she had never used before going to Paris. The next semester she tried again, and this time made it into the top 30, but here discrimination intervened. She was rejected again, without explanation, but a French acquaintance informed her that the examiners had arbitrarily lowered her score to keep her out. Like many gatekeepers of male-dominated professions, they were willing to resort to exceptional measures to exclude women, even flagrant cheating.

Morgan was undeterred. In October of 1898 she took the exam once more, and this time ranked 13th. Left with no excuse to reject her application again, the school was compelled to reluctantly accept her, and her studies began. She was not out of the woods, though. One of the requirements of the program was participation in a series of public design competitions, for which entrants were required to be younger than 30. Morgan at this time was already 27, giving her only three years to complete a course of study that took most students, including her mentor Bernard Maybeck, five. Working with an intense determination, she entered the contests and managed to earn enough credits to graduate just short of her thirtieth birthday.

Shortly after graduating, amid much fanfare from San Francisco newspapers, Morgan returned to her hometown to begin her career. She became California’s first licensed female architect, and in 1904 set up her own practice. Morgan was a detail-oriented and innovative architect with several characteristic touches, such as a fondness for reinforced concrete, which paid off handsomely in new commissions during the city’s rebuilding after the 1906 earthquake. Her early training in civil engineering also made her a master of structural design, whose buildings were noted as much for their superb construction as for their aesthetic qualities.

Morgan’s most famous commission was the monumental Hearst Castle at publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon estate. The castle, which Morgan designed, refined and elaborated over a period of nearly three decades, became one of the most luxurious private residences in the world and inspired many imitators, including the fictional “Xanadu” that serves as the setting for Orson Welles’ landmark film Citizen Kane. Though most of her buildings were nowhere near as ostentatious as Hearst Castle, she brought to all of them the same flair for decoration and sense of organized style.

More than many, in fact more than several of the other Achievers discussed in this series, Julia Morgan was a professional driven by passion for her work. She lived a simple life with few luxuries, never married, and seemed to have little interest in celebrity. It was her fascination with the technical aspects of architecture, and her determination to be the best, that saw her through both the good and bad times of her career. Her dedication to the craft seems to strike a chord with many professional architects even today. Just a few years ago, in 2014, the American Institute of Architects awarded her a posthumous Gold Medal, their highest honor. Morgan is the first woman in history to receive this particular honor, but thanks in large part to her own example, we can be sure that she will not be the last.

Next Post: Robert Sengstacke Abbott, the newspaper publisher whose Chicago Defender led the charge for black solidarity and self-improvement across the country during the years of the Great Migration.