Not all the harmful prejudices that hold us back from mutual respect and cooperation are based on visually apparent traits like race or sex. The fine gradations of polite society have given most of us an abundance of criteria that we use to judge people based on their personal history and choices. Among these one of the most often overlooked is bias based on a person’s level and type of education.

University alumni often dismiss graduates of vocational colleges as tradespeople who didn’t have the brains to attend a “real” school; in return, vocational college graduates often write off university students as eggheads who only know what they read in books. Driven by the important role they play in most people’s lives and careers, different college experiences have given rise to a host of unpleasant stereotypes, often tending toward the idea that academic and practical knowledge are bitter enemies. Yet many of the greatest scientists in history were people who worked hard to obtain both, such as Miguel Ondetti, an Argentinian-American chemist who discovered one of the first important heart medications.

Miguel Angel Ondetti was born in Buenos Aires on May 23, 1930. His parents were working-class members of Argentina’s burgeoning Italian population. Young Miguel was fascinated by scientific experimentation from an early age, but coming from a family of limited means he had no chance to live the life of an ivory-tower scholar. By age 16 he was working during the day and studying at night at a “commercial” high school in the city. After graduating, he applied to the University of Buenos Aires, hoping to continue his studies, but he was soon to receive a terrible shock.

The university, it turned out, only accepted applicants who had received a baccalaureate from an accredited academic high school. Ondetti’s diploma, obtained from a vocational school, apparently didn’t count for anything. Rebuffed, but determined to get in, he audited afternoon classes at a second high school while working an early shift as a bookkeeper for the Department of Energy, until finally he satisfied the entry requirements. Ondetti had hoped to study biology, but he soon found that a strong grounding in chemistry was necessary to understand his chosen field, and he spent five years in the university’s chemistry program before obtaining a licentiate degree in 1955.

Just before Ondetti graduated, one of the university’s top chemistry professors, Dr. Venancio Deulofeu, had accepted a job at the Argentinian branch of the reputable Squibb Institute for Medical Research. Deulofeu invited Ondetti to apply for a research training scholarship offered by the institute, and after a week of indecision he accepted a job at Squibb. For several years he studied alkaloid chemistry there while working on a PhD in chemistry, which he finally received in 1960. Both his academic endeavors and his work at the institute were about to pay off, for that same year he was offered a job at Squibb’s primary research facility in New Jersey, and he and his wife decided to travel more than five thousand miles to a new home in the United States.

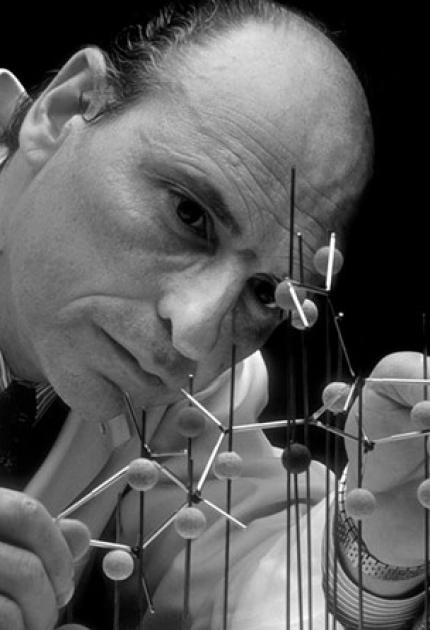

At the Squibb facility in New Jersey, Ondetti began his career synthesizing the organic amino acid compounds known as peptides, which were believed to be a promising field for pharmaceutical development. Though Ondetti had hoped to work on steroid research, he soon became fascinated by peptides and the variety of biological functions they performed in the human body. He was especially intrigued by two peptides called angiotensin and bradykinin, which raised and lowered blood pressure by contracting and expanding blood vessels respectively. By analyzing the venom of a Brazilian pit viper, Ondetti and his team were able to synthesize a drug that would inhibit the action of angiotensin and prevent bradykinin from breaking down; in other words, a potential cure for hypertension, one of the most common forms of heart disease.

Unfortunately, this “ACE” (angiotensin-converting enzyme) inhibitor could only be produced in small quantities, and tests of its effectiveness were inconclusive. The Squibb Institute began to see peptide development as a dead end in the late 1960s, and soon afterward it decided to move on to other forms of research. Still, Ondetti was not daunted, and in March of 1974 he went back to work on the project without official approval, certain that more research would lead to a breakthrough product. His expectations were realized two years later, when his team patented one of the world’s first heart medications: captopril.

Ondetti’s leading role in developing captopril made his reputation in the pharmaceutical field. The drug was influential both for its effects and for the revolutionary way it was designed. After 1980, when captopril was approved for use in the United States, numerous other ACE inhibitors sprang up in its wake, and several of these are still prescribed today to treat hypertension. Ondetti himself rose through the ranks at Squibb to become senior vice-president of cardiovascular and metabolic research by 1990, and the next year he was awarded the prestigious Perkin Medal for commercial chemistry research. In 1999 he and fellow Squibb scientist David Cushman received the Lasker Award for contributions to medical science in honor of their work on captopril and the benefits that stemmed from it.

Two personal traits kept Miguel Ondetti going through years of setbacks: tenacious dedication to his work and relentless curiosity. When he was prevented from attending a great university, he studied and worked on his own until he had the credentials to attend. When he was directed away from specialized fields where he wanted to work, he found inspiration in the work before him and connected it back to his own interests. And when the most important project of his life was threatened by changing attitudes at the Squibb Institute, he worked tirelessly to reconcile his own work with the new goals of his organization. Life would be a lot more peaceful if we all worked just as hard to reconcile the conflicts, both internal and external, that we encounter.

Next Post: Anna Akhmatova, the Russian poet who risked her life and freedom criticizing the Soviet regime during the height of Stalinism.