In the United States today, the idea of “famine” is something we tend to associate with fiction and the distant past, not our own lives. News stories warn us of housing troubles, poverty and homelessness, but not of nationwide food shortages that endanger human lives. Yet throughout most of history people across the world have lived in fear of starvation. Countries like Mexico and India, despite their huge size and abundant farmland, were net importers of grain well into the 20th century, and population-growth pessimists like Paul Ehrlich dismissed the hope that they would become self-sufficient as sheer fantasy. Famine had struck these nations many times before, and the received wisdom was that the passage of time would only make things worse.

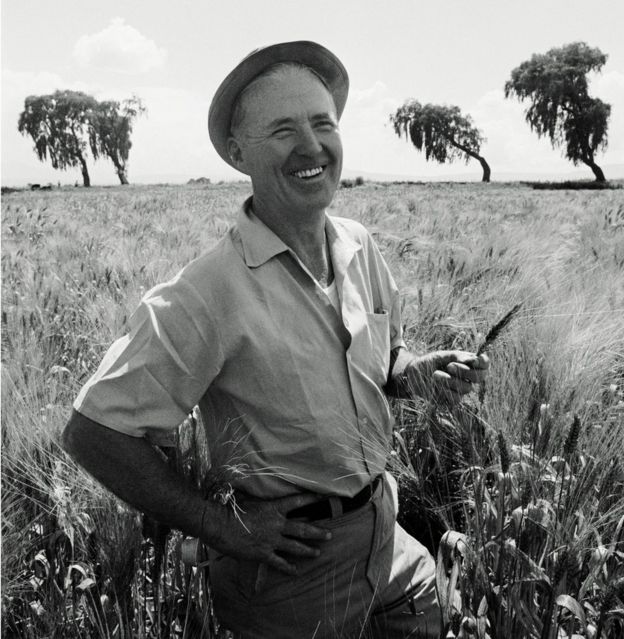

Shockingly, reality did not bear out the expectations of these doomsayers. Mexico introduced disease-resistant varieties of wheat that increased yields dramatically, changing it from a net importer to a net exporter in barely a decade. India closed its food gap a mere six years after Ehrlich published a book that branded this outcome as impossible. All around the world, crop yields were increasing, famine was disappearing, and the prospects for developing countries were better than they had been in centuries. This “Green Revolution” has been credited with rescuing nearly a billion people from the threat of starvation, and it might never have happened if not for the dogged and determined efforts of the agronomist Norman Borlaug.

Norman Borlaug was born on March 25, 1914 in Cresco, Iowa, on a farm that belonged to his grandparents, who were themselves the children of Norwegian immigrants who had come to America in the mid-19th century. For most of his childhood he lived simply, working on his grandparents’ farm and attending a one-room county schoolhouse through the eighth grade. After graduating from high school, he applied to the University of Minnesota, but failed its entry exam; fortunately, he was accepted into the university’s newly founded General College and soon managed a transfer to the College of Agriculture’s forestry program.

To put himself through college, Borlaug worked for several years with the Civilian Conservation Corps and the U.S. Forest Service in the late 1930s. Budget cuts forced him out of the Forest Service shortly after he received his degree, and with the encouragement of professor Elvin Stakman he decided to become a specialist in plant pathology. This would prove to be a fateful decision, but its importance didn’t become apparent for several years as World War II intervened. Borlaug tried to enlist, but was turned down as his research skills were considered more valuable. Instead, Borlaug worked at DuPont for most of the war, developing chemical products for the armed forces. Then, in 1944, he was finally given the chance to put his knowledge of plant biology to its best use as part of a joint initiative sponsored by the Rockefeller Foundation and the government of Mexico, the Cooperative Wheat Research Production Program.

Mexico had been struggling for some time with two major threats to its wheat crop: poor soil and the parasitic fungus known as stem rust. Borlaug, who had studied methods of preventing rust at college, immediately set to work attempting to breed a strain of wheat that would resist the rust. But just as quickly he began to encounter opposition, not only from local farmers who distrusted his experiments, but even from his own team. When Borlaug suggested speeding up the breeding process by growing two test crops a year instead of one, his boss flatly refused. He believed, incorrectly, that the seeds couldn’t grow that fast, so it would only waste more resources. Borlaug became so frustrated that he left the project, only returning when his old professor, Elvin Stakman, visited the project site and persuaded his boss to attempt two plantings.

After nearly two decades of research and crossbreeding, Borlaug and his team were able to produce two high-yield, rust-resistant varieties of wheat which they called Pitic 62 and Penjamo 62. These wheat strains were an enormous success, expanding the country’s wheat crop to six times what it had been when the project began in 1944. Buoyed by this success, Borlaug began to make plans for testing the wheat in other parts of the world. In early 1962 the Indian Agricultural Research Institute tested several of his strains, and soon after the head of the institute, M.S. Swaminathan, asked Borlaug to visit India and bring his samples along. This was exactly what he had hoped, and despite the hazards of war on the Indian subcontinent, resistance from conservative government officials, and the lack of available funds for shipping, he managed to send several hundred tons of seeds to agricultural installations across India.

From this small foothold, the Green Revolution would eventually grow to cover all of India and Pakistan. Even as authors and academics across the first world were forecasting humanity’s inability to feed itself, crop yields in India slowly but steadily grew and overtook the population increases which so many had feared. In many parts of the developing world during the late 1970s famine began to seem like something that belonged to the past and not the future. Secondarily, but importantly for Borlaug, who was an avid conservationist, the improvement of yields on existing land made it unnecessary to clear more land for farming, preserving millions of acres of undeveloped wilderness.

Despite the many benefits that Borlaug’s innovations brought to humanity, the man himself received surprisingly little recognition for much of his life. This has a lot to do with his character and attitude toward his work. Borlaug was a humble, retiring man who preferred to spend his time researching and arranging the details of his projects, not boosting the image of those projects in the media or marketing himself. When attention did come his way, it was often negative; environmental and social activists accused him of subverting traditional agriculture, encouraging too much reliance on monocultures, and using “unnatural” methods to increase crop yields. Borlaug did not hesitate to push back against these allegations, seeing them as extremely misguided. In an interview from the late ‘90s, he had this to say:

“Some of the environmental lobbyists of Western nations are the salt of the earth, but many of them are elitists. They’ve never experienced the physical sensation of hunger. They do their lobbying from comfortable office suites in Washington or Brussels. If they lived just one month amid the misery of the developing world, as I have for fifty years, they’d be crying out for tractors and fertilizer and irrigation canals and be outraged that fashionable elitists back home were trying to deny them these things.”

Next Post: Vivienne Malone-Mayes, the mathematician and educator who studied in the face of race prejudice to obtain her PhD and become one of the first black math professors in Texas.