Designers of private homes have often been given short shrift by the historians of architecture, who tend to focus on grander and more impressive structures: skyscrapers, monuments, museums and the like. In some sense this would appear perfectly appropriate; public buildings, after all, reach the widest group of viewers and take the most time and effort to construct. Even so, the humble house shapes our everyday experience in a much more immediate way. There are millions of people in the United States who will never see the Chrysler Building, but who see houses of every shape and size all around them.

Private houses, especially those belonging to celebrities, do appear in glossy magazines and books about interior decorating, but these are something to read over for a week and then throw away. Public architecture, it would appear, is the only kind of building that exists for all time. Houses belong to the here and now, while a skyscraper or an opera house belongs to history.

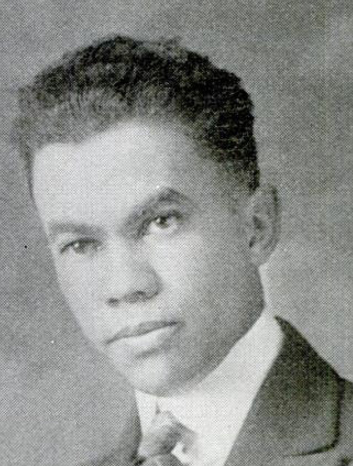

Today we’re taking a look at an architect whose greatest work was in the field of designing private homes, but whose legacy has earned him a place in the history books: Paul Revere Williams, the first licensed African-American architect west of the Mississippi.

Williams’ struggles started before he even entered school. Orphaned at the age of four, he and his siblings were placed in separate foster homes in Los Angeles, where his parents had moved from Memphis a few years earlier. Though he was fortunate to have a foster mother who cared about his education, his chances of being able to follow his dreams seemed slim. During his high-school years, a presumably well-meaning teacher warned him not to choose architecture as a career, because white clients would be reluctant to hire him and black clients would not be numerous or wealthy enough to support him.

But Williams was adamant. He felt that quitting now would lead him into an unbreakable habit of self-defeat. And so he continued his studies, becoming certified as a building contractor in 1915 and earning his license to practice as an architect in California in 1921. In 1923 he became the first African-American member of the American Institute of Architects, and he soon gained a reputation as a versatile and imaginative architect for all kinds of buildings: shopping centers, tennis clubs, office blocks, and acres upon acres of private homes.

Contrary to the dire predictions of his would-be mentors, Williams had picked an ideal time to enter the building trade. Southern California was growing in the 1920s faster than it ever had before, and architects were in high demand. His mastery of many different styles endeared him to the newly-minted celebrities of Hollywood, who were eager for the latest styles and conveniences to be installed in their homes. New suburbs like Bel Air and Beverly Hills began to fill up with Williams-designed houses, often designed to harmonize with their surroundings and offer the best possible views.

Williams’ reputation eventually grew to the point that he was able to work on more prestigious projects. His interior remodeling of the Saks Fifth Avenue store in Beverly Hills was admired for making each department feel like a boutique, rather than one section of a huge shopping complex. He was tapped to design several memorials, including one for the “Unknown Sailor” at Pearl Harbor. Late in his career he also took on futuristic styles, helping to design the Los Angeles Airport’s “Googie”-styled Theme Building and even working out plans for a space-age monorail in Las Vegas.

Having achieved success despite discouragement from his surroundings, Williams was determined to encourage the young people who followed him. He labored over designs for hospitals, Baptist churches, and the 28th Street YMCA, the first in the city built for an African-American public. Immediately after the war, he both designed and worked in Broadway Savings and Loan, a banking institution that was dedicated to providing home loans for black GIs at a time when many banks refused to. Williams felt that having a home to be proud of was crucial to being a good citizen; he once said that “expensive homes are my business and social housing is my hobby.”

Having designed more than 2500 buildings in a career spanning half a century, Williams retired in 1973 with a legacy that any architect would be proud to own. And while he may deserve to be better remembered, he has already achieved the recognition among his peers that more famous architects possess among the general public. In 2017 the AIA voted to award him a posthumous Gold Medal, their highest architectural award and one that is only given to architects whose work has had a lasting influence on the discipline. Williams is the first African-American architect to receive this award.

Next Post: Emik Avakian, the Armenian-American inventor with cerebral palsy who dedicated his mind to assisting people with physical disabilities