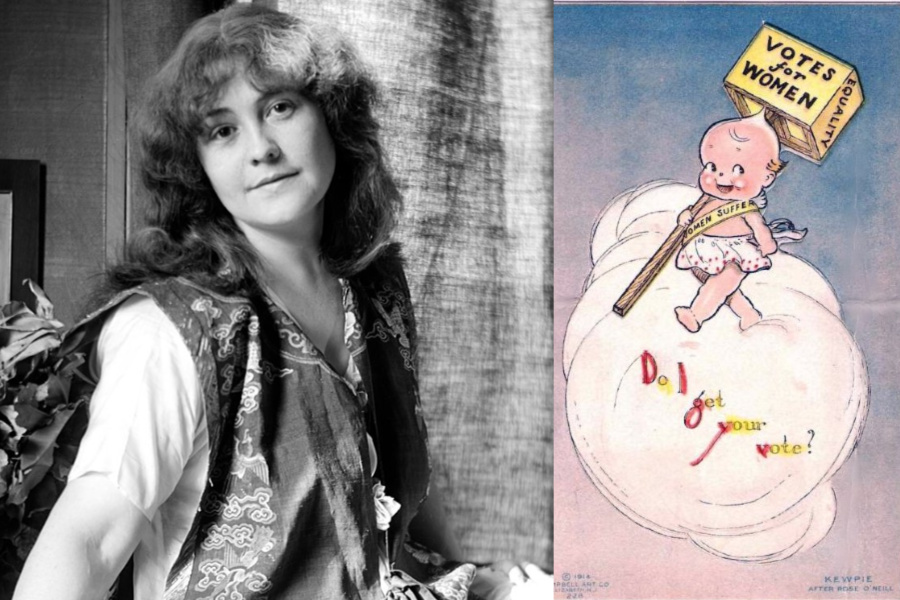

We often think of our personal and professional lives as being two separate spheres, with “success” in each appearing very differently and requiring different skills. Despite their differences, however, our experiences in either sphere have major repercussions in the other, both good and bad. Career-related conflict and frustration can make a person irritable and aggressive toward their friends and family; by contrast, having a fulfilling personal life can lead a person to accept difficulties at work with a certain amount of detachment and calmness, making them more effective. One woman who struggled to keep her career afloat as personal disappointments threatened to engulf her was the illustrator Rose O’Neill, inventor of the cherubic cartoon creatures known as Kewpies.

Rose O’Neill was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania in 1874 but moved with the rest of her family to rural Nebraska at a young age. Her father was a bookseller who travelled the country, and both of her parents were fond of music and the theater. They encouraged their daughter to draw, and she showed considerable artistic talent, winning local drawing competitions and selling illustrations to newspapers in Omaha. By her early teens she was already helping to support her family, supplementing her father’s uncertain income.

O’Neill and her family parted ways when she was 19, her family moving to a small homestead in Missouri while she made her way to New York hoping to become a professional illustrator. For three years she lived in a convent, attending meetings with editors in the company of an escort of nuns. In September of 1896, a comic strip she had written was published in Truth magazine, the first published comic strip in the United States made by a woman. The next year she rose even higher, beginning a six-year run on the staff of Puck magazine as its only female employee. Within a few years her work was circulated nationally in advertisements as well as Harper’s Magazine and Life.

But just as her professional life was thriving, O’Neill’s personal life brought disillusionment. As a teenager in Nebraska, O’Neill had encountered an attractive, charming man named Gray Latham. Latham continued to write letters to her after her move to New York, eventually coming to visit her in person, and in 1896 the two were married. He stayed at her family’s home in Missouri, Bonniebrook, while she continued to work in New York and saw him only when she came back to visit her relatives.

Latham’s charm, and the fact that she spent a great deal of time away from him, may have kept O’Neill from noticing his less attractive qualities. Latham was a man of expensive tastes, a playboy who liked to gamble and live it up without any interest in working to earn the money his lifestyle required. O’Neill sent much of her earnings home to support her family, and Latham was able to take this money and spend it on himself without her approval, often without her knowledge. At times, he even drew her paycheck before she had gone to the office to collect it, exploiting his position as her husband at a time when “the man of the house” was implicitly trusted as a responsible figure.

O’Neill endured this parasitic behavior for five years, but there was a limit to her patience, and she finally divorced Latham in 1901. A year later she became romantically involved again, this time with a fellow Puck employee, Harry Leon Wilson. Wilson was less of a cad than Latham had been, but his marriage to O’Neill was similarly short-lived; he was apparently a moody and depressed man, and although he had worked up the energy to court her, the romantic bond between the two was weak. They ultimately divorced in 1907, and throughout the rest of her life she never married again.

In another curious bit of irony, O’Neill’s last great romantic disappointment came only two years before her greatest creative triumph, the invention of the rosy-cheeked “Kewpie” figure inspired by Cupid, a universal symbol of love. The Kewpies were characterized as kind but slightly mischievous creatures who solved people’s problems in unexpected and amusing ways, akin to fairy-tale helpers like the diminutive cobblers from “The Shoemaker and the Elves.” This appealing premise eventually blossomed into a worldwide phenomenon, with Kewpies appearing on every kind of merchandise imaginable, but most often observed in the form of a “Kewpie doll,” a small doll made out of bisque and famously offered as a carnival prize almost everywhere in the United States. The success of the Kewpies ultimately made O’Neill the highest-paid female illustrator in the world.

Although her personal experiences with love were difficult, Rose O’Neill made her Kewpies with the hope of spreading a message of love to the world. She wasn’t averse to other kinds of uplifting messages either, such as when she used a Kewpie in a popular postcard advocating women’s suffrage, a cause she ardently supported. In the world of the “New Woman,” with her own job, her own tastes, her own magazines and newspapers, O’Neill was a constant reminder of how much women could achieve.

Next Post: Garrett Morgan, the businessman and inventor who wrestled with race prejudice to promote a life-saving smoke hood